Getting Unstuck

When coding, we often either

- Get stuck in the middle of coding a particular section, without knowing how to proceed

- Don't even know how or where to start

Even once we're done with a section, there are three main ways something can go wrong:

- The code isn't doesn't compile or interpret successfully

- The code compiles, but an error is produced while it's running

- The code compiles and runs, but doesn't do what we want it to

In any case, it can be hard to determine where our problem is or even where to start when making a fix. This isn't something that goes away! It's something we continuously learn to manage as programmers.

This guide serves to help you get unstuck.

How to start

Sometimes the hardest part of coding, especially when we're learning a language for the first time, is figuring out where to even start. There are two main steps to writing successful code:

- Developing an algorithm to solve the problem

- Figuring out how to code our algorithm

Example

Let's say I give you three numbers, and ask you which of the three is the smallest. For example, I give you the numbers [3,7,1], and you need to determine somehow that 1 is the smallest.

First, we develop an algorithm:

- Compare the first two numbers, and keep the smaller of the two.

- Compare the two remaining numbers, and tell me the smaller of the two.

With our [3,7,1] example, we first compare 3 and 7. 3 is smaller, so we throw out 7. Then we compare 3 and 1, and say "1 is smallest."

Now that we've developed an algorithm, we just have to translate our algorithm into Python code. The easiest way to do this is to take the algorithm you've written, and put it in your source file as comments:

# 1. Compare the first two numbers, and keep the smaller of the two.

# 2. Compare the two remaining numbers, and tell me the smaller of the two.

and then writing our code in between the comments:

# 1. Compare the first two numbers, and keep the smaller of the two.

smaller = min(number1, number2)

# 2. Compare the two remaining numbers, and tell me the smaller of the two.

our_min = min(smaller, number3)

print(f'{our_min} is smallest.')

Asking for help

If you are stuck with how to start,

- Identify which step you are having trouble with. Are you having trouble figuring out how to solve the problem, or are you stuck on how to translate your algorithm into source code.

- Formulate a specific question about what you need help with

- Make a Piazza post, or ask for help in Office Hours

Step 2 is by far the most helpful for us. If you say "I am stuck on Todo 2", we have to essentially walk you through this process to figure out how to help you. Questions we'd love to answer are

- I'm having trouble with developing an algorithm to solve Todo 2, specifically with

x. - I know how to solve Todo 3, but I'm having trouble converting this step of my algorithm into Python code.

Stuck in the Middle

If you get stuck in the middle of coding a section, there are often two things that can be causing the block:

- You aren't sure what the next step in your algorithm is

- You aren't sure how to convert the next step of your algorithm into code

If you're finding yourself stuck because you don't know the next step in your algorithm, take a break from coding and try to write out your entire algorithm. Psuedocode and control-flow diagrams are both very useful in outlining your full algorithm. In either case, if you're still stuck, see the Asking for Help section above.

Another reason you can get stuck in the middle of a section is that you have come up with a solution, but are stuck on how to write an efficient or "clean" solution. Our suggestion here is that you either

- Finish your current implementation, and then go back and tidy up specific sections.

- Restart entirely. Run through your algorithm top to bottom before you start to code anything, and look for things you can fix.

The first suggestion often works better if your algorithm is solid, but you weren't quite sure the best way to implement one part of the algorithm. The second suggestion is better for cleaning up an inefficient algorithm.

This is not something that goes away! Even as advanced programmers, we will get halfway through coding a section, and think

Well, I know how I can finish this function, but it's going to end up really messy. Do I restart, or will this be manageable to tidy up later?

This is a balancing act that you will get better at handling the more complicated problems you tackle.

Warning and Error Messages

Once we're done coding, there are two main types of errors we can get,

- Compilation or interpretation errors: the source code we've written isn't valid Python

- Runtime errors: our source code is valid, but the code performs an unexpected action while running

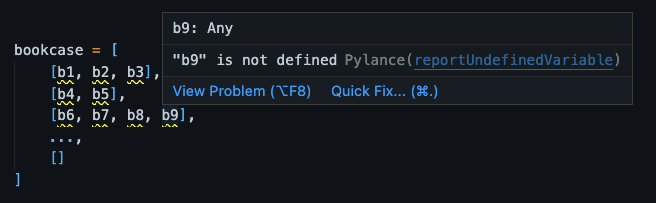

In VSCode for Python, there is a program called the linter. The linter reads through our code, looking for syntax or style issues.

How to fix a problem detected by the linter will obviously depend on the problem, but the linter broadly categorizes problems. VSCode will display issues detected by the linter by drawing a squiggly line under the problematic code segment. The color of the squiggly line will change depending on what type of problem was detected:

- A red underline signifies an error. The linter will produce an error if thinks there is a bug in your code.

- A green underline signifies a warning. Warnings mostly appear under functions names we have misspelled, under variables we declare and never use, or under variables we attempt to use before they are declared.

- A blue underline signifies information. In python, this usually means the code segment will run fine, but is bad practice, or is "old" python.

In any case, if you hover over the underlined code, the error, warning, or information message will appear, often times indicating what you need to fix:

What your linter considers an error, warning, or information will depend on what linter you install. Find more information on linter messages here. The VSCode Python extension uses Pylint by default.

The underline colors listed above are the default colors. Your theme may change the color of the underlines.

If you are red-green or green-red color deficient, I highly recommend changing your warning underline color from green to a different color. I use yellow. For a guide on how to do change your warning colors, see the Change Linter Colors guide.

Unexpected Errors

Although the linter will detect many errors, there are some errors that the linter will not detect (at least by default).

For example, say we have the following code:

text = input("What would you like to type?\n")

third_character = text[2]

print(third_character)

First, we get some input string, and store it in text. Then, we get the character at index 2 of text (the third character), and store it in third_character. Finally, we print third_character out.

As written, this code will result in zero messages from the linter. However, this doesn't mean nothing can go wrong. What if I just say Hi? There's only two characters, so happens when we try to access the third character? In Python, we will get the following message back:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/path/to/example.py", line 2, in <module>

third_character = text[2]

~~~~^^^

IndexError: string index out of range

This is an error message. This is essentially Python's way of saying, "Something unexpected just happened, here's the problem we identified and what we were doing when it happened." More specifically this is what's called a traceback: Python has "traced back" it's steps to figure out:

- What happened?

- Where are we? What file are we in, and on what line? Are we in a function call?

- What steps did we take to get here? Did we make multiple nested function calls? If so, what function calls did we make?

The first line of the error message should always read

Traceback (most recent call last):

This line identifies an error occurred, and tells us that, if the error lists multiple function calls, the most recent function call is listed last (in other words, the problem happened in the last line listed).

Next we have a series of code snippets of the form

File "/path/to/example.py", line 2, in <module>

third_character = text[2]

~~~~^^^

Each of these snippets lists

- The snippet itself, in this case

third_character = text[2] - Where the code lives,

File "/path/to/example.py", and on what line,line 2 - If the snippet is in a function, denoted as

in function_name, or not in a function, denoted asin <module>. Code not written in a function is sometimes called "top-level" code.

In this instance, the error message also tells us that the error is specifically in the attempt to access text[2], and not in the assignment of text[2] to third_character. In this case, we'd say that "line 2 throws an error", or "accessing text[2] throws an error."

Finally, the error message will list the name of the specific error that occurred. In this case, we have

IndexError: string index out of range

which indicates that we're attempted to access the element of text at an index that doesn't exist.

See the Common Errors guide for tips on how to approach various specific errors.

More complicated errors

With more complicated code, your error might have multiple successive snippets listed. For example, if we make a function call, and then the error occurs inside the function call, like in:

def print_name(name):

print('My name is ' + my_name)

print_name('John')

Python will print out the location of each nested function call made, then the location of the code snippet where the problem happened. In this instance we get the following error message:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/path/to/print-name.py", line 4, in <module>

print_name('John')

File "/path/to/print-name.py", line 2, in print_name

print('My name is ' + my_name)

^^^^^^^

NameError: name 'my_name' is not defined

There are two snippets: first the function call print_name('John'), which is listed as in <module> since it's "top-level" code, and then inside the function call we have print('My name is ' + my_name), which is in a call to the print_name function, so it is listed as in print_name.

This gives us a sense of what the function call stack looked like at the time of the error, since each successive snippet is a nested function call, with the last line being where the error occurred.

Conditional Errors

It's possible that you sometimes get an error when you run your program, but not always. In our first example, giving an input of 3 characters or more will not cause an error, because there would be a third character to access. However, sometimes our program will return an error, like when we input Hi.

If you only get an error sometimes, but not always, you should figure out

- Is the error always in the same place?

- Is it always the same error message?

- Is the code snippet using some sort of user input?

Probably the most common error to get sometimes, but not always, is an IndexError, especially if you're accessing an index of user input. Say we're assuming that a user is going to give us a four digit binary number, and we want to check if the one's digit is less than 6. A bad way to check this would be

number = input("What 4-digit number would you like to check?\n")

digit = int(number[3])

print(digit < 6)

Why is this bad? Well, what happens if the user gives us a three digit number? number[3] will throw an IndexError.

If you don't always get the same error, or the error isn't always in the same place, you likely have multiple errors. It's possible that one of them always happens, and the other only happens sometimes, but happens before we get to the error that is always there.

Unexpected Output

Say our code has run without any error, but the code isn't doing what we want it to. For example, your program runs successfully, but prints the wrong thing. This is where we largely get into the realm of debugging. Getting rid of error messages is also debugging, but it can be much easier to guess what might be going wrong from an error message than it is from an incorrect, but error-free output.

There are four main ways of debugging:

- Rereading your source code and looking for bugs

- Putting print statements in various places to check values of variables or what parts of your code are/aren't being executed

- Using the debugger

- Writing unit tests

Manual Debugging

Rereading your source code is probably the easiest way to find small errors, so it's highly recommended in the beginning when your code is short. The main downside of this is that, if you've been coding for 2+ hours straight, it's often hard to look for errors in the code you've been staring. If you've ever written a paper and come back the next day to find lots of grammatical or spelling errors, this is the same idea. It can get hard to spot errors in code you've spent a lot of time looking at.

Take a break before you start debugging. Seriously. If you've been coding for a couple hours straight, implementing your algorithm and getting rid of error messages, the best thing to do is take a quick, 30 minute break and come back to it, especially if you're under a time crunch.

Print Debugging

Print debugging, sometimes referred to as "caveman debugging", is the most brute force approach. It consists of just putting print statements in various parts of your code to check both what parts are/aren't running and values of variables. Print debugging is effective for small projects where you have a good idea of what is going wrong, or finding what region of your code has the problem. However, if you don't quickly find what is wrong, have a multi-file project where many things could be going wrong, or have multiple underlying problems all at one, print debugging can take a lot of time. You might spend hours changing values of print statements, commenting prints out or back in, and running your code over and over again after each change.

The Debugger

As the name suggests, the debugger is the most powerful tool for finding bugs in your code. Like how the Python interpreter runs your code line by line, the debugger lets you step through your code's execution line-by-line. As your code runs, the debugger will show you

- What local variables are declared and their values

- The state of the function call stack

- Terminal output as it happens

The debugger lets you put break points at specific lines in your code, letting you run the program up to a certain point, and then pausing execution, giving you a snapshot in time of how your program is running. You can also set conditional breakpoints, like "stop at this line only if i is 3". For this reason, the debugger is essentially a strictly stronger version of print debugging.

For a tutorial on how to use the debugger in VSCode, see the debugger guide.

Print Debugging vs the Debugger

When it comes to choosing between print debugging vs using the debugger, print debugging is useful if you have a good hunch about what is wrong, and just need verification where things are going wrong.

For computer science and informatics students planning on taking more programming languages in the future, we highly suggest you learn to use the debugger now. In less "user-friendly" languages like C, debuggers are objectively more powerful than print debugging for things like picking up segmentation faults. (Aside: these are like Python errors, but instead of immediately giving you the error message and where it happens, C dumps a record of your computer's recorded working memory and says "here's what went wrong!", which is a lot less fun to read. A debugger will just stop where the segfault happened, and show you what all the variables were, without you having to read through the core dump).

We as programmers still use print debugging all the time. But knowing how to use a debugger is an important skill, so we recommend you learn as early as possible, especially while we're working with a "user-friendly" language like Python.

Unit Tests

Say you're writing a calculator app, and you've implemented the following underlying math functions:

def add(a, b):

...

def subtract(a, b):

...

def multiply(a, b):

...

def divide(a, b):

...

def exponential(a, b):

...

You press all the buttons on your calculator, and expect it to evaluate subtract(add(3, multiply(4, 5)), divide(exponential(10, 2), 2)) and out the result of (3 + 4 * 5) - (10^2)/2 = -27. However, you're calculator gives you a result of -2.

How do we know where the problem is? Is it with your calculator buttons? Do the buttons work, but the calculator has an order of operations problem? Is there a problem with one of our math functions?

What we can do is we can write a set of tests for each separate function, where we pass it two inputs, and check the output is what we expect. For example, we could call add(2, 3), and then check that it returns 5. We call these tests unit tests, they're a series of tests that make sure the building blocks of our program work in isolation. The idea is that, if we know each of our functions work in isolation, then the problem is in how we call them, or in our algorithm.

In Python, we often use assert for unit testing. An example of a set of unit tests for the above code would be

assert add(2, 3) == 5

assert add(9, 0) == 9

assert subtract(5, 2) == 3

assert subtract(2, 9) == -7

assert multiply(5, 2) == 10

assert multiply(3, 0) == 0

assert divide(9, 1) == 9.0

assert divide(10, 2) == 5.0

assert exponential(4, 2) == 16

assert exponential(2, 5) == 32

You want your unit tests to cover all inputs. For example, here we'd want to check that our functions all work how we'd expect with positive numbers, negative numbers, floats, and any special cases like 0 for divide and exponential.

Unit tests often work best in tandem with another debugging technique. For example, if all of these pass, we can assume that our math functions work, and that our problem is actually that we're using our functions improperly. So we boot up the debugger, and pin down that the problem is in the order of operations conversion section (the example I gave does (10/2)^2, not (10^2)/2).

Unit test are often the bulk of your grade on programming assignments. We check that all of your functions work how we ask them to, and then once we know all your functions are working test that your project works as a whole after that.